November is invariably upon before we know it. For those of you in the southern hemisphere, temperatures are starting to ramp up and summer is approaching. Here in Scotland, though, the clocks went back in late October; it’s dark and dreich. A chap feels dolorous. Desultory.

Meteorologists reckon November is the most gloomy and depressing month of the year due to reduced atmospheric pressure and increased cyclonic activity, which forms clouds. Prolonged lack of sunlight contributes to the onset of depression in some humans so one way of countering this could be to spend more time with family and loved ones, as well as attending the cinema, theatre or exhibitions etc.

Given the pandemic, this isn’t as simple as it once was. Here at chez Letford this month, therefore, the mind veers to poetry. As Dylan Thomas put it: “A good poem is a contribution to reality. The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. A good poem helps to change the shape of the universe, helps to extend everyone’s knowledge of himself and the world around him.”

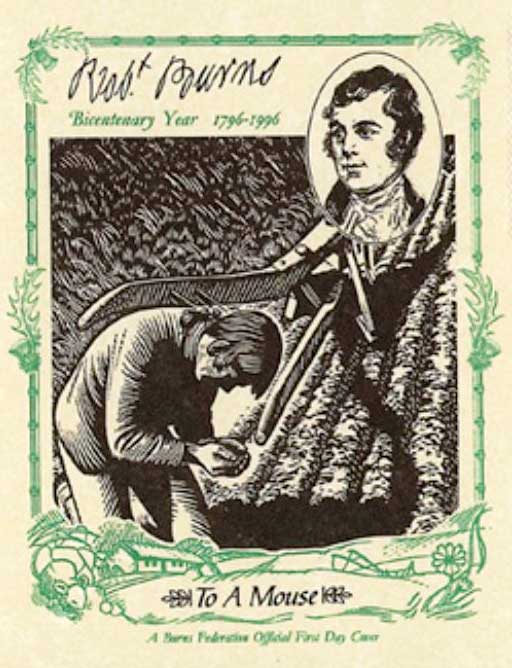

Did you know that one of Burns’ most famous poems, To a Mouse, was written after something Burns experience one November? The full title of this poem is, as you probably know, To a Mouse, On Turning Her up in Her Nest with the Plough, November 1785. It’s probably the most famous poem about a mouse ever written and is based, clearly, on a real event.

Thy wee bit housie, too, in ruin!

It’s silly wa’s the win’s are strewin!

An’ naething, now, to big a new ane,

O’ foggage green!

An’ bleak December’s winds ensuin,

Baith snell an’ keen …

However, for the piper, the ideal poem to read this month comes from Robert Garioch (1909-1981), the Scottish poet and translator who wrote in Scots.

Garioch (pictured) penned The Big Music in, I think, 1971. Many of you will probably know of his shorter work, Sisyphus but The Big Music is worth a read. I last read it in 1991 whilst studying Scottish History at Glasgow Uni. but I re-discovered it the other day. In his poem, Garioch perceptively evokes the sonic world of the GHB – something many pipers can’t even do!

The poet centres the poem on a piping competition in London. With the London Competition taking place this weekend, here is a snatch of the piece. I’d like to have been able to include the poem in its entirety but for obvious reasons this is not possible. Ha’e a keek then out it seek:

The Big Music

Victoria Street in London, the place gaes wi the name,

a Hanoverian drill-haa, near Buckingham Palace,

near the cross-Channel trains, Edinburgh coaches,

Army and Navy Stores, an ex-abbey, a cathedral,

near the Crazy Gang, the ‘Windsor,’ Artillery Mansions,

no faur, owre the water, frae the Lambeth Walk,

near the exotic kirk-spire carved wi’ the Stars and Stripes,

disappointed nou, a frustum, whangit wi’ a boomb.

This great Victorian drill-haa is naethin like Scotland,

binna the unco hicht and vastness of the place.

The judges jouk into their tent; the piper treads the tarmac.

His gear lemes in the sunlicht of hunner-and-fifty-watt suns,

while we in the crowd luik on, MacAdams and Watts wi’ the lave.

Skinklan and pairticoloured, the piper blaws life in his wind-bag,

aefald, ilka pairt in keeping, the man, his claes and the pipes,

in keeping wi’ this place, as tho he stuid in Raasay,

Alaska, India, Edinburgh Castle, of coorse, for that maitter,

like a traivler I met in the rain on the Cauld Stane Slap, and him dry;

like the Big Rowtan Pipe itsel, that can mak its ain conditions,

as the blaw-torch brenns under water in its ain oxygen-bell,

like the welder’s argon island, blawn in the thick of the air,

sae the piper blaws his ain warld, and tunes it in three octaves,

a steil tone grund on the stane, and shairpit on the ile-stane,

like a raisit deil, mair inexorable nor onie ither music,

for the piper cannae maister this deevil of the reeds,

binna to wirry him aathegither, and brek the spell.

Nou, jaggit as levin, a flash of notes frae the chanter

slaps throu the unisoun, and tines itsel in the drones,

no jist richtlie in tune; the snell snarl dirls wi a beat,

sae the piper eases the jynts of the drones, and tries again,

and again, and again, he fettles the quirks of his fykie engine,

flings the fireflaucht of melody, tined an octave abuin the drones,

bass drone and twa tenor drones geynear in tune on A,

wi a michtie strang harmonic bummlan awa on E,

that the piper is ettlan to lock deid-richt in tune wi the chanter,

for the pipes are a gey primitive perfected instrument,

that can fail a fine piper whiles, as his art may fail,

tho it warks in the tradition of the MacKays of Raasay,

guairdit throu generations of teachers and learners and teachers,

and thon piper staunds forenenst us, skeelie in mind and body,

wi’ the sowl, a mystery greater nor mind and body thegither,

that kythes itsel by virr of its presence or absence in music.

etc.

• Incidentally, I am reliably informed that in his own manuscript copy of the poem, Garioch wrote: “Nae need of scenery. This is hard music, not theatrical – you don’t look at the loch while you listen to this big music. A Drill Hall in Victoria Street is as good as anywhere else.” I’m sure Robert Reid would agree with this sentiment!

• Robert Garioch: Collected Poems can be bought here.

.

• The views expressed in all blogs that appear on Bagpipe.News are not necessarily the views of the National Piping Centre.