• From the September 2005 Piping Times

By Bruce P. Gleason, Ph.D

When medieval European mercenaries showed up to recover the Holy Land during the Crusades, they were met by Muslim warriors on at least one occasion (1291 at Acre) being led into battle by kettledrummers on the backs of camels. The ominous sight and massive sound so frightened and impressed the western forces that they brought the custom back to Europe, which, over the following 600 developed into a tradition of military musicians on horseback throughout much of the world – initially as solitary signallers and later in bands. By the 19th century mounted bands numbered in the hundreds, and varied in size and instrumentation from a few trumpeters accompanied by drummers, to full concert bands on horseback.

As a direct extension of France and the United Kingdom (both of which continue to maintain centuries-old mounted band traditions) Canada would seem to be a logical place for the tradition to continue. The custom, however, was fleeting, with individual bands – including several within the North-West Mounted Police, and a beautifully attired mounted band of the early 1930s of the Governor General’s Body Guard in Toronto – each of them lasting only a few years. Another even more unusual one of these short-lived bands was the Pipe Band of the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles during World War I, and, as the name implies, it consisted of bagpipers and drummers on horseback.

Standing alongside her allies in World War I, Canada offered what would finally total 619,636 soldiers (424,589 serving in Europe) in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), as the Canadian army raised during the First World War was designated. Serving mainly in France, Belgium, and England, the CEF was comprised of infantry units (including mounted rifles), artillery batteries, medical units, communication units, engineering companies, and railway and forestry troops, as well as a cavalry brigade and scores of military bands.

The mounted rifle battalions were probably a result of Canada’s participation in the Boer War as part of the Empire, whereby there was a general concern about the Boer tactics causing havoc to conventional martial procedures of the day. Canadian military officials saw a need for dealing with this type of enemy by training more sharpshooters — and mounting them on horseback. This seemed like a natural for Western Canada with cowboys and the North- West Mounted Police, etc., so there was a concerted effort started in the early 1900s to develop mounted rifle contingents with a depot set up in Winnipeg where recruits were sent for training, and then dispersed to a number of Western centres designated to form Mounted Rifles.

The military bands of the CEF were part of an age-old custom of musicians accompanying soldiers into battle, although by this point, bands were performing mainly in ceremonies and encampments rather than amidst combat. Bagpipes, however, which had been used in battle for centuries, were still being played in the thick of things in WWI, as well as during route marches, burials and rest periods, with more than 500 from Scottish Regiments being killed, and another 600 wounded. Canadian Militia regiments had maintained pipe bands (most of which were affiliated with Scottish regiments) at least since 1816 with the 5th Royal Highlanders. During WWI, there were pipers with many Canadian Regiments overseas including the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry the 13th, 15th, 16th, 19th, 21st, 25th, 26th, 29th, 42nd, 43rd, 46th, 48th, 67th, and 85th Infantry Regiments, the 107th (Pioneers), the 35th (Forestry) Battalion, and the 1st and 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR).

While mounted bands of brass, woodwind and percussion instruments were common within the armies of several countries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mounted bagpipers were rare – although not unheard of. Writing in 1927, Charles A. Malcolm, in The Piper in Peace and War, indicates that Piper Loudon, the piper of D Company of the 1st Battalion (formerly the 91st Highlanders) of the Princess Louise’s Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, made quite a showing when he debuted along with the rest of the company in South Africa in 1883 on horseback. As well, after the South African War of 1899- 1902, Malcolm relates that within the Scottish Horse, “on the long marches across the veldt of South Africa, the pipers, mounted on trained Russian ponies, played cheerful airs for the men.” Further east, the 17th Bengal Cavalry hosted a mounted pipe band in India of pipers and a kettledrummer at the turn of the 20th century – and at the date of writing, the Royal Stables of Oman continues to host a camel-mounted pipe band.

While little information is available about the pipe band of the 4th CMR, which had been raised in Toronto, several records mention the band of the 1st CMR, which was initiated by officers of the 1st CMR in December 1914 under Pipe Major Ian Stewart (“Stuart” in some writings), and later led by Pipe Major Angus Morrison. Recalling the training period, veteran piper Rod J. MacKay wrote in 1960:

“We were approached by some of the Officers to have a try at a Mounted Band. So try we did, and were surprised at the manner in which our Horses responded to all the noise of the Pipes and Drums. Many of our Mounts were quite fresh off the Range, and we had a squad of Bronco Busters Saddle breaking them for a start.

“They were all thoroughly trained in a matter of weeks, all of them were trained to knee guidance — for direction, and they kept perfect step while the Band was playing.”

When I asked Lt. Col. Roy Wearne, past supervising bandmaster of the Omani 3rd Band Squadron (who has more than 40 years of equestrian and mounted – band experience) what he thought of this statement, his reply was: “… it would be absolutely impossible to train horses to march in step!” Further, since the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) had given up the idea of mounted bands a decade earlier because of the difficulty in training the horses, the additional task of training horses to march in step is unlikely. An unusual aspect of the 1st CMR mounted pipe band was that it apparently only served mounted during the initial and concluding stages of its existence. A rare newspaper mention of the pipe band appeared in the Thursday, May 20, 1915 edition of the Brandon Weekly Sun, which recorded the battalion’s 22 mile journey to Camp Sewall for final training before heading for Europe:

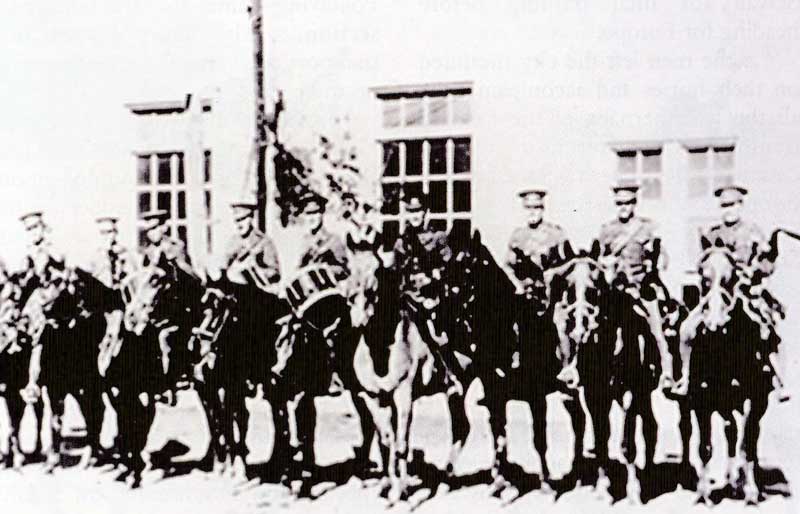

“… the men left the city, mounted on their horses and accompanied by all the paraphernalia of the military transport. Col. Stevenson was in command and there was a total of 550 troopers and 600 horses… The route was McTavish Avenue via Twelfth Street north to Rosser, and thence east to First Street and on to the main trail for Sewell. At the head was Regimental Segt.-Major [Charles] Casey, an old Brandon man, whose life ambition seemed to have been realized. The bagpipe band was mounted, and the horses behaved well…Col. Stevenson and Major Andross were at the head of the first squadron and the signalling section, then followed the mounted troopers. Following came the machine gun section…. The heavy horses, the transport and guard wagon brought up the rear.”

MacKay recalls that the band was 19 strong when they left Brandon, but was dismounted upon arrival in France with members being converted to infantry, where their jobs included stretcher bearing and working with ration parties. This conversion was not unusual, and in fact was based on a centuries-old precedent for military musicians. Although several pipers were killed in battle, the band was reorganised towards the end of the war, and appeared on Dominion Day, July 1, 1918, in the Corps Sports and Ceremonial Parade at Tinques, France. Historian, Victor W. Wheeler describes this performance in The 50th Battalion in No Man’s Land (1980):

“The most unusual and thrilling sight of the colourful occasion was the spectacular March Past of the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles, 8th Infantry Brigade, 3rd Division. The Regiment was led by a mounted Pipe Band of 12 pipers and eight drummers, and their beautiful chargers visibly enjoyed their splendid role to the tune of their Regimental March Past, Highland Laddie.”

It is difficult to say what the impetus was in initiating the short-lived mounted pipe band of the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles. The originators would have been aware of the Canadian connections to Scottish regiments and piping traditions, but were also probably looking to form some kind of unique unit. Whatever the case, this band holds an interesting place in military music history.

• Dr. Bruce Gleason, associate professor of graduate music education at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minion USA, holds degrees in music (B.A., Crown College) and music education (B.S. and M.A., University of Minnesota, and Ph.D., University of lowa). A veteran army musician (euphonium player with the 298th U.S. Army Band of the Berlin Brigade, 1989- 1991), he is the head of the Institute for Military Music Research and is tracing the tradition of horse-mounted bands from the time of the Crusades to the present. His work has appeared in the Journal of Band Research, Renaissance Magazine, St. Thomas Magazine, the Irish American Post, National Guard Magazine, MHQ: the Quarterly Journal of Military History, and the Journal of the International Military Music Society,

• Postscript: We are grateful to Iain Bell of Langholm, Scotland for the following:

“Private Richard Maybin was originally from Lisnamurrican, Broughshane, Co. Antrim in Northern Ireland but like many of his generation left and settled in Canada (Saskatoon). With the outbreak of the First World War, he enlisted in the 1st. Canadian Mounted Rifles at Manitoba as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

“After landing in France on September 22, 1915, as stated in the article above, they soon found that the foul muddy conditions of the Western Front made their horses a hindrance and by January 1916 the Canadian Mounted Rifles, complete with pipes & drums were dismounted and re-organised as infantry. In the run up to the Somme offensive the Canadians entered battle at Mount Sorrel on June 2, 1916 and Pte. Maybin, aged 21, was killed that day.

“Richard’s personal effects and his bagpipe were returned to his grieving mother, Margaret Maybin at Lisnamurrican where they lay concealed in a trunk in her attic for more than half a century before being re-discovered and restored by Harold Bennet of Carricklongfield, Dungannon.

“In 2016, I was privileged to have this tune judged by the R.S.P.B.A. (NI) as the slow air to be presented to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, commemorating Pte. Maybin and those of his generation who never came home. The tune was given it’s first ever public airing by Pipe Major Ian Burrows who played it on Private Maybin’s own bagpipe.

“Richard Maybin is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in Ypres, Belgium and also at 1st Broughshane Presbyterian Church, where I’m humbled to note they have a framed copy of this slow air on display.”

Iain Bell’s tune for Maybin can be found in his collection published in 2018 called From Scots Borderer to Ulster Scot.