By ANDRA NOBLE

Roderick – Roddy – Sutherland Ross, who died in Grimsby, Lincolnshire on August 13, 2016, aged 95, was a well known name in piping. He was a noted piper and author of Binneas is Boreraig, the acclaimed six-volume work on the piping of Malcolm Macpherson.

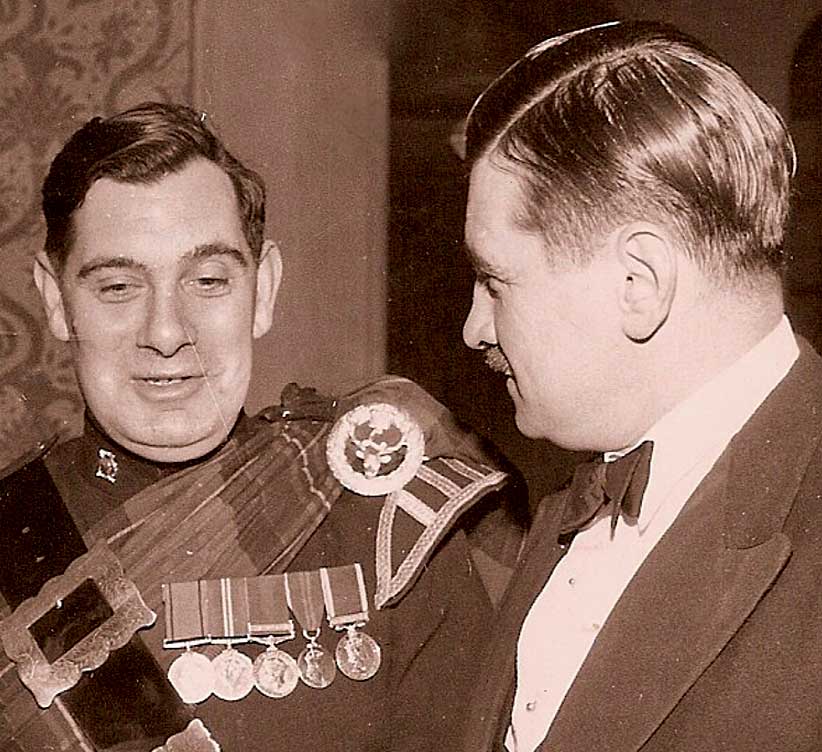

Roddy, pictured in 2005, was born at 30 St. Albans Road, Edinburgh, the youngest of the five children of the Reverend Dr. Neil Ross and his wife, Helen Annand. Another son Neil, a lawyer, died in 2008, the three other siblings many years ago. Dr. Neil Ross was born in Glendale, Skye. As a child he witnessed the land reform struggles there. He trained for the Christian ministry, as did his brother, Alexander who eventually became an Assistant Chaplain General to the Scottish Command; until 1987 the post of Chaplain General could only be held by an Anglican clergyman. Dr. Ross, after ministries in St James, Kirkcaldy, Rosemount, Aberdeen and Buccleugh in Edinburgh, became parish minister at Laggan Bridge near Dalwhinnie in Badenoch from 1923 until his death in 1943. Laggan Bridge is also only a few miles from Catlodge, where Calum Piobair lived.

As ‘Ross of Laggan,’ Neil was a ‘weel kent’ figure in the kirk and throughout the Scotland of his day, and he was involved prominently in Scottish Gaeldom. To his Doctorates of Divinity and Literature, the latter for his thesis on the book of the Dean of Lismore, was added in 1938 a CBE for his services to the National Mòd. A piper of some ability, he won the Pibroch Challenge Cup in 1925 and was President of the Mòd at Fort William in 1934, which Ramsay MacDonald attended while Prime Minister. Dr. Ross delivered an address in Gaelic at the inauguration of the MacCrimmon cairn at Boreraig in 1933 at which John MacDonald, Inverness and Robet Reid piped.

Such then was the distinguished background to Roddy’s early life. Sons of the manse or rectory, however, do not automatically become saints but occasionally, loveable sinners.

Neil and Helen Ross had lost their first son in his infancy and, for that reason, it is thought Helen encouraged Roddy to study medicine, which he did at Edinburgh University, graduating with first class Honours. Apart from piping, among his hobbies were playing shinty and putting the shot. On graduation, war service followed in the Royal Army Medical Corps; posted to India he was later parachuted into Burma where, among other matters, he had to deal practically with the victims of rape and torture by the enemy. After the war he was called as an expert witness to the war crimes trials in Malaya.

Returning to civilian life, Roddy was in General Practice, spent largely in Edinburgh, though he did locums in Ontario, Saudi, the United Arab Emirates, Wales, and in the Falklands after the war there. Two or three times he practised as a prison doctor and for a time was superintendent of a geriatric ward in Scathro Road Hospital, Grimsby. Many stories are told of his time in practice in Edinburgh; by no means all of them can be told here.

We may first reflect on the words of Albert Morris, sometime columnist of the Scotsman newspaper, who says in his book, Kay’s Capital Characters, “Edinburgh at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, was a hard drinking capital with professional citizens often indulging in high spirited, bizarre actions.” Had Roddy Ross lived in that earlier age in Edinburgh of which John Kay wrote, there can be no doubt that Kay would have immortalised him in his ‘Original Portraits.’ As it was, Roddy’s frequently turbulent professional and social life in the Edinburgh of the second half of the 20th century did not pass unnoticed and unappreciated by the people and press there, and some of his escapades have entered into the city folk-lore of that era. Stories abound.

Still fondly remembered are his parties at home and his appearances at the West End Hotel in Edinburgh, then still the haunt of the highland diaspora in the city. Kenny MacDonald of Pitlochry first saw and heard Roddy in the hotel one Hogmanay, playing Highland Wedding on his pipes. They became good friends. Roddy introduced Kenny to Malcolm Macpherson and together they taught him pibroch. On occasion, Roddy, not driving at the time, gave Kenny lessons in a taxi, hired by the good doctor so he could visit housebound patients. When Roddy could drive, he sometimes took piping friends over the Forth Bridge to a sheltered piece of land nearby, owned by a relation. There they would, in turns, march up and down playing pibroch, while criticising each other’s playing; so, heard but not seen, they unwittingly created the legend of the ‘Phantom Pipers of the Forth Bridge.’

One lady, who occasionally attended his parties, recently told me that they were lively affairs, with Roddy and his wife generous hosts and the mainly business and professional guests thoroughly enjoying themselves. She remembers an eminent Edinburgh advocate (of the law but not of temperance) always gave a very polished vote of thanks as the party drew to a close. Occasionally, while entertaining at home or in the hotel, Roddy would be moved to declaim with great effect, lines “of a bloody and robust nature,” from Aytoun’s Lays of the Scots Cavaliers. A particular favourite being the poem, Charles Edward at Versailles, in which the luckless prince, later in life on the anniversary of Culloden, meditates on the hammer blows of fate on that fateful day. Piping after Culloden features in the poem, but not the hoped for, Pibroch loud and shrill; instead “The bagpipes fitful wailing … a dirge both low and solemn …” marking the end of the Stuart dream.

A Hebridean friend of Roddy’s, but not a patient, was passing his surgery and suffering from a sudden skin irritation, thought that Roddy might help, so he called in. The waiting room was full and he was about to turn away when Roddy, by chance, opened the surgery door, saw him and immediately asked him in Gaelic to come in to the surgery, then in English said to the waiting patients, “This man is an urgent case.” Quickly writing out for him a prescription in the name of a patient who rarely needed a doctor, Roddy then took a half bottle and two glasses from a filing cabinet. Drams were taken, and Roddy played a pibroch or two to his friend, who eventually asked about the waiting patients. The reply? “If they are really ill, they will stay; the malingerers will go.” Leaving shortly afterwards, the waiting room was found to be nearly empty.

In a skit at a Christmas pantomime in Edinburgh at the time, two Morningside spinsters are seen meeting up for coffee at Jenners, the former independent department store on Princes Street. One remarks to the other; “My Jean, you’ve put on weight!” Shamefacedly, the answer came, “I may be pregnant.” Her friend’s comment, “Well Jean, you’ll just need to have a word with Roddy Ross,” brought the house down with laughter.

Roddy helped to organise the interment in Laggan Bridge kirkyard of Malcolm MacPherson’s ashes. Just beforehand, Roddy poured large drams for the mourners, malt that had been given to him in part payment for certain services rendered to the girlfriend of a Grangemouth docker. In those pre-container days, one cask of a shipment of malt whisky, awaiting export in a warehouse in Grangemouth docks, was ‘accidentally broached,’ to the immediate benefit of the dockers, and later, the mourners.

As the mourners stood silently around the grave, there was a sudden loud explosion. Roddy had detonated a quantity of gelignite, sourced from a miner friend, again in lieu of ‘professional fees’. Shotguns of varied quality were discharged then Roddy played his pipes, marching around the kirkyard, after which George Clark, a highland games heavyweight athlete, planted a rowan tree. The explosion, the gunshots, the piping and the planting of a rowan tree were, Roddy said, traditional measures to scare away witches and evil spirits from the interment.

These measures were only partly successful. Certainly, no witches have been seen at the cemetery since, but ‘evil spirits’ were much in evidence at the celebration afterwards.

In 2007, Roddy and his second wife, Julie, moved to Grimsby to be near their daughter there. On Saturday afternoons he would attend, with great enjoyment, the practice sessions of the North East Lincolnshire Pipe Band. There, and in his home, he was very happy to teach anyone interested in ceòl mòr.

Piping played a big part in his funeral; the band led the hearse from the Grimsby Crematorium gates up to the door, playing Green Hills of Tyrol and The Rowan Tree. At the start of the service John Fraser played the ground of I Gave a Kiss to the King’s Hand, as Roddy had taught him. Later, Jim Beedie played The Wandering Piper, and as the mourners left the service, Herbert Such played Lament for MacLeod of Colbecks.

Roddy’s life reminds us that the lives of flawed characters are often the most interesting.

* Taken from Andra Noble’s article, Roddy Ross, a capital character, that appeared in the January 2020 edition of the Piping Times.

• With thanks to Kenny MacDonald, Pitlochry, and other former patrons of the West End Hotel in Edinburgh. Thanks also to Roddy’s son, Lindsay.

In 2009, Jack Taylor captuted footage of Roddy speaking at the Piobaireachd Society conference in Fisher’s Hotel, Pitlochry describing the emotions behind the Finger Lock and other tunes:

Malcolm Ross MacPherson was born in 1907 in Newtonmore and died by his own hand in Edinburgh on November 4, 1966. He was named after his grandfather, Calum ‘Piobair’. Malcom’s mother was Alice Gertrude Ross – Mrs MacPherson of Inveran – and when he was a baby, he wouldn’t sleep until his father, Angus had sang pibroch to him.

Malcolm began piping aged seven and was taught by his father and by his uncle John (‘Jockan’). In 1923, aged 16, he competed at The Northern Meeting and placed fourth in the Gold Medal (his father was first). He placed first in 1927.

Malcolm had a huge impact on piping. In 1926 at Kyleakin Games in he placed joint first with John MacDonald of Inverness, then at his peak and who was teaching him at this point. Malcolm won all the major prizes of the day many times over. Roddy Ross said that Jockan MacPherson believed Malcolm to be a better piper than himself and Calum.

In contrast to the brilliance, there was a sad and troubled side to Malcolm’s life, involving failed relationships and drinking problems. For a time he worked as the Factor on the Achany estate and then in 1940 he enlisted in the Cameron Highlanders but was invalided out a year later as a chronic alcoholic. Malcolm settled in Edinburgh. His first marriage broke up, leaving two children, and he then had a son from another relationship before embarking on a second marriage, which also broke up, leaving a son, Euan.

In Edinburgh, Malcolm collaborated with Roddy Ross on the production of the Binneas is Boreraig books and records.

Malcolm took his own life in Edinburgh in 1966. Much that could never be regained died with him. He was buried in Lagganbridge churchyard beside his grandfather, Calum Piobair. In this quiet churchyard, next to each other, lie grandfather and grandson, two of the greatest masters of piping of all time.

At the funeral, John MacLellan played Lament for Patrick Òg MacCrimmon from the church and Lament for the Only Son after the burial (Malcolm was Angus and Alice’s only child). According to his father’s wishes, no headstone was erected until after Angus’ own death. Alice also lies in the Laggan kirkyard.

There was apparently a family connection between Roddy Ross and Malcolm but so far it has not been identified definitively.